The Moulin Rouge originally was a hotel and casino located in West Las Vegas, Nevada, that is listed on the United States National Register of Historic Places. The first desegregated hotel casino, it was popular with many of the black entertainers of the time, who would entertain at the other hotels and casinos and stay at the Moulin Rouge.

The Moulin Rouge opened on May 24, 1955, built at a cost of $3.5 million. It was the first integrated hotel casino in Las Vegas, perhaps in the nation. Until that time almost all of the casinos on The Strip were totally segregated—off limits to blacks unless they were the entertainment or labor force.

The hotel was located in West Las Vegas, where the black population was forced to live. West Las Vegas was bounded by Washington Avenue on the north, Bonanza Road on the south, H Street on the west, and A Street on the east.

It was during this era that Will Max Schwartz saw the need for an integrated hotel. Will, along with other investors, including boxing great Joe Louis, built and opened the Moulin Rouge at 900 W. Bonanza Road. This placed it in a prime location between the predominantly white area of the strip and the largely black west side. The complex itself consisted of two stuccoed buildings that housed the hotel, the casino, and a theater. The exterior had the hotel's name in stylized cursive writing and murals depicting dancing and fancy cars. The sign was designed by Betty Willis, creator of the "Welcome to Las Vegas" sign on the south end of the strip.

When it opened, the Moulin Rouge was fully integrated top to bottom, from employees to patrons to entertainers.

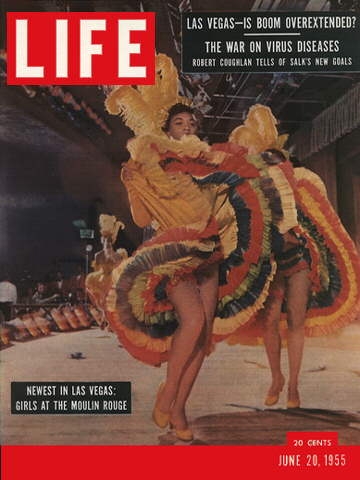

The hotel made the June 20th, 1955, cover of Life magazine, with a photo of two showgirls. A veritable "A" list of 50s- and 60s-era performers regularly showed to party until dawn. Great black singers and musicians such as Sammy Davis Jr., Nat King Cole, Pearl Bailey, and Louis Armstrong would perform often. These artists were banned from gambling or staying at the hotels on the strip. In addition, white performers including George Burns, Jack Benny, and Frank Sinatra would drop in after their shows to gamble and perform. Eventually management added a 2:30am "Third Show" to accommodate the crowds.

The hotel made the June 20th, 1955, cover of Life magazine, with a photo of two showgirls. A veritable "A" list of 50s- and 60s-era performers regularly showed to party until dawn. Great black singers and musicians such as Sammy Davis Jr., Nat King Cole, Pearl Bailey, and Louis Armstrong would perform often. These artists were banned from gambling or staying at the hotels on the strip. In addition, white performers including George Burns, Jack Benny, and Frank Sinatra would drop in after their shows to gamble and perform. Eventually management added a 2:30am "Third Show" to accommodate the crowds.

In November of 1955 the Moulin Rouge closed its doors. Some say it was a victim of casino oversaturation (the Moulin Rouge was one of four new hotels that ran into major financial difficulties that year). Some say it was poor management. The exact cause will probably never be known. By December 1955, the Moulin Rouge had declared bankruptcy.

The short but vibrant life of the Moulin Rouge helped the civil-rights movement in Las Vegas. For a while the hotel was owned by the first African American woman to hold a Nevada Gaming License, Sarann Knight-Preddy. Many of those who enjoyed and were employed by the hotel became activists and supporters. The hotel was also the spark needed to bring an end to segregation on the strip.

In 1960, under threat of a protest march down the Las Vegas Strip against racial discrimination by Las Vegas casinos, a meeting was hurriedly arranged by then-Governor Grant Sawyer between hotel owners, city and state officials, local black leaders, and then-NAACP president James McMillan. The meeting was held on March 26 at the closed Moulin Rouge. This resulted in an agreement to desegregate all strip casinos. Hank Greenspun, who would become an important media figure in the town, mediated the agreement.

In 1992 the building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Although the Moulin Rouge complex remained shuttered for decades, many plans had been hatched to rebuild and reopen the cultural landmark. But on May 29, 2003, a fire ripped through the buildings, almost entirely gutting the complex. No witnesses have ever been found, no one has come forward with information leading to the cause of the fire, and to this day all that remains is the facade with its signature stylized name.

January 2004 saw the Moulin Rouge sold again to the Moulin Rouge Development Corporation. The stylized "Moulin Rouge" neon sign was turned back on.

For at least the third time in the past four years, the Moulin Rouge has announced it will rise again, this time propped up by a Virginia-based company's investment.

The Bonanza Road hotel's owners, headed by Brothers Dale Scott and Rod Bickerstaff, presented their casino and hotel construction plans to the community in February 2008, in a public meeting at their offices east of the hotel. The stakes were high because the Moulin Rouge is one of only about 20 local listings on the National Register of Historic Places — and the only one connected to civil rights. Though open for less than 12 months in 1955, the Moulin Rouge was a hotel and casino where blacks and whites partied together. It became a symbol of integration. In 1960 casino owners, the NAACP and others met at the site and agreed to end segregation on the Strip.

Starting in 2004, owners of the property began announcing that the Moulin Rouge would return to glory, and add a museum. At least two attempts failed. In 2008, Republic Urban Properties, based just outside Washington, D.C., said it will invest up to $1 billion in a 700-room hotel, with restaurants, a concert hall, stores and gambling. The announcement was carried in reports around the country, but those familiar with the site are skeptical about the plan. The property is in a run-down neighborhood, near one of the valley's largest homeless shelters.

Rainier Spencer, director of the UNLV Afro-American Studies program, says owning the Moulin Rouge is "really a privilege," given the site's historical importance for blacks in Las Vegas and nationwide.

Next Month: The entrepreneurial vision to raise the Moulin Rouge.

www.mrdcnv.com